If you enjoy Mothers Under the Influence I invite you to subscribe for $5/month. Paid subscribers receive a bonus edition every month. Last month’s paid-tier edition was called The Poetics of Rudy Jude.

Many of us have spent the last two years getting acquainted with the limitations of the nuclear family, a social configuration whose stock is way down. Caregiving is lonely and relentless in these times, and workplaces are slow to realize this, so for primary caregivers who also work outside the home, life has felt impossible. And yet, unlike almost any other institution — marriage, even — the nuclear family persists.

There are many scholarly entry points for understanding what the nuclear family reinforces and how it has come to be the hegemonic structure of the Western home. Studies on consumer capitalism, Western imperialism, laws of coverture (those old laws that subsumed a woman’s rights and property to her husband upon marriage), Protestantism, and American manifest destiny all offer explanations of how and why the nuclear family has come to be our common unit of measure for home-making.

So how do momfluencers strengthen the hermeneutics of the nuclear family? (*Hermeneutics means a method of interpretation, or a way of understanding something, or as Foucault called it, “truth games”. I kind of regret not titling last month’s newsletter Hermeneutics of Charcutics.)

Who’s around to do the shitwork? A visit to my family archive

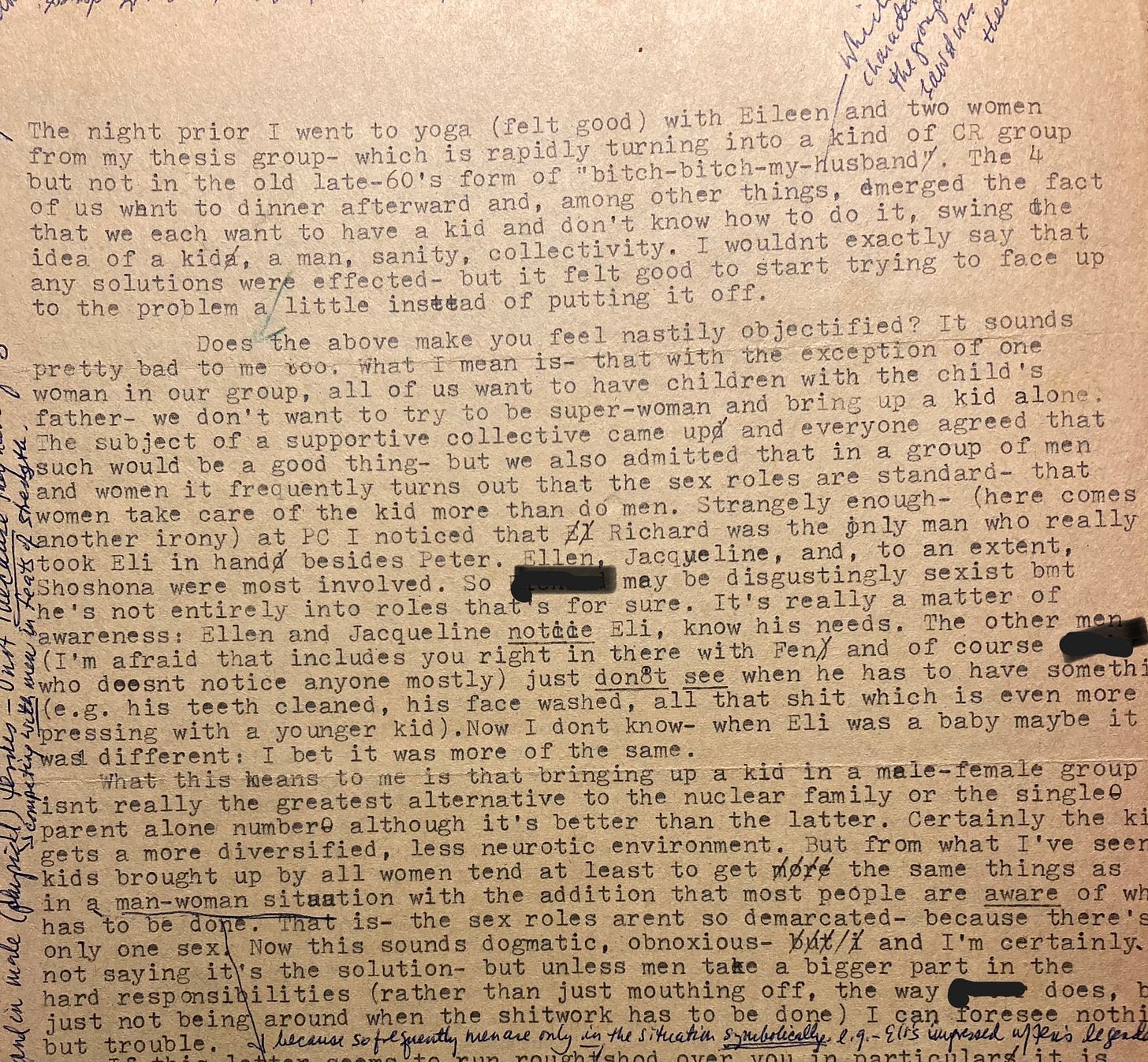

Let’s examine some primary source material from 1980 before we begin. Last year, after my mother died, I received a box of old letters that she had written to my father before I was born. For the first few years of my parents’ relationship, my father was living on a commune he had co-founded in Vermont, and my mother was finishing her dissertation at McGill in Montreal and teaching. So they wrote a lot.

In this letter below, my mom explains to my dad she is interested in having a kid (who will be me), but she’s not sure she can stomach a nuclear family. Commune life, as she observes it at PC (Packer Corners, my dad’s place) was not much better. (I redacted the names of the folks my mom casually insults in this letter! And I send love to Eli, who was a baby then and is now a proud father of 3.)

The reason I’m sharing this letter is to note that the conversation about what to do instead of a nuclear family is not new. My mom observes that on the commune, intentions don’t seem to matter that much when it comes to apportioning work. The women end up being the ones who notice the needs of children, and attend to them.

A lot has changed since 1980: Queer families have rights and visibility, more men are caregivers. But the impasse my mom describes - that a heterosexual nuclear family contains gender conventions that even a communal household might not be enough to unsettle, and that those conventions coalesce and become malignant around the requirements of care work - has not budged in the 42 years since.

The black box theory of nukefam representation

On Instagram, momfluencers are pretty much always part of a nuclear family. And by this I mean: These people don’t even have neighbours. (Obviously they do IRL, but remember, I’m talking about the representation here!) Non-family caregivers occupy a hypothetical shadow-realm where their existence is speculated about in the comments, and every so often, in a moment of Ask Me Anything-fueled magnanimity, a momfluencer will disclose how often she has childcare, and the audience showers her with praying-hands and clapping-hands emojis, and thanks her for being “real.”

But multigenerational, multifamily living is absolutely not it for momfluencers on Instagram. There’s a sprinkling of single moms out there, and a few moms who have come out as queer and now co-parent with their exes while in new relationships. This latter form of representation is very recent, only having emerged in the last year or so. Why are we only seeing the nukefam?

The French sociologist Bruno Latour has a theory of “black boxes” in science. When a consensus is established about a popular scientific idea, we put it into a “black box,” which enables us, as a society, to progress forward. If we didn’t put agreed-upon scientific truths in black boxes, and instead kept their tenets perpetually up for debate, scientific progress would be impossible because we would always be rehashing the basics. By being black-boxed, some scientific concepts are “rendered invisible by their own success.”

*cough*vaccines*cough*

I think of the nuclear family on Instagram in a similar way. When women began monetizing their family-life content in the early 2010s, they looked to the accounts that had early success; those were often Mormon or Mormon-adjacent trad wives. Seeking the same path to financial independence, many women imitated the aesthetics of these early successful momfluencers. This meant mom, dad and the kids. Other caregivers — the fact of care as labour at all, in fact — were simply not relevant to this kind of storytelling. They introduced threads of narrative that were hard to maintain.

I believe that for an ordinary mom to become a momfluencer, she must black-box her family arrangement as “nuclear.” She must put aside questions of non-traditional care and housekeeping in order to concentrate on the complex work of representing herself online.

(As I mentioned in the interview I did last year with AHP’s newsletter Culture Study, one exception to this rule that I loved was Ree Drummond, who was always sharing anecdotes about her friend Hyacinth and the various cowboys working for her husband, and the foods they refused to eat. But the folksy, expansive world she was narrating could accommodate this kind of peopling, and most other mom-worlds cannot.)

The consumer capitalist underpinning of all of spon con naturally privileges family self-reliance; no brand wants to partner with a mom who tells us about how she shares a car with her in-laws. We, the enlightened fans of Rudy Jude, can barely countenance the fact that Julie and Tony live on the same piece of land as Julie’s mom. Freeloaders!!!

Twas thus that in the first few years of Instagram spon, the nuclear family was black-boxed. The nuclear family is what family on Instagram came to mean. Any other family representation would require explanation and justification, and in a highly competitive algorithmic environment, a lot of text explaining who someone in a photo is, and what role they play in the family group, is not going to do anything at all for engagement.

It’s a bummer. Scientific knowledge belongs in black boxes when it becomes agreed-upon by the scientific community. But the nuclear family and the Instagram algorithm are both social constructs, not scientific facts. What family means should perpetually be up for debate, everywhere. If we don’t, we’re forcing people who want to experiment, to suck it.

The necessary affective rollercoaster of the nukefam

One goal of non-nuclear households is more fairness in the work of housekeeping and caregiving. In theory, this means establishing a smooth clicking-along of domestic life, where folks have time for hobbies, and no one’s a superhero or a martyr. Work is rendered more visible and there’s a lot of it, but no one has to do more than their share.

A bureaucracy of chore charts, emails and spreadsheets is imposed - or, if it’s an intergenerational household rather than a communal one, a regime of repetitive conversations and vaguely annoying check-ins. But with the work spread out, the days are meant to pass as gentle rolling hills, not mountains to scale day after day. Is that a whiff of monotony?

The nuclear family is disaster capitalism to the co-op or multigen household’s social welfare state. Or, to push the metaphor even further, the nuclear family is alcoholism to the sobriety of shared care. The highs of the nuclear family are VERY high, and the lows are terrifying. But along with these high and lows come useful affective scripts, and these help us act out the mile-markers of adulthood on social media — and IRL. Affective scripts teach us how to act as we take on certain social roles. Before a 30-something woman becomes a mother, she already knows how moms-today talk, because she’s been exposed to affective scripts of nukefam motherhood for years, via her friends and social media.

I’ve read that one of the scary parts of getting sober has to do with affective scripts: not knowing how to be, or how to feel, in circumstances where you used to always be on something. As a mother in a nuclear family, I have sometimes felt myself leaning on the drama of nukefam life to give shape to my social relations. “We NEED a girls’ night!” makes sense after weeks of nuclear parenting. If I were living in a group, with lots of accountability and shared work, how would I justify my need for cathartic release? It feels gross to admit this but I would be remiss not to.

One of the ways that influencers influence us is by giving us these affective scripts — think of the wine-mom staggering through Target cracking jokes, or the breastfeeding mama’s conscientiousness, or the “boy mom” (I struggle with that one, since I “am one”) who’s always game for anything. These scripts are thin and boring, but they are what we have. Success on Instagram’s algorithm does not readily afford more nuanced scripts than this. There is no gram-ready affective script for the mom who shares the work of raising kids with five other people, who is in fact not exhausted, who leaves the family for periods of work or rest without feeling guilty. What kinds of memes does this mom share with her group chat? I have no idea.

Towards a process of unqueenification?

When husbands appear in the mamasphere, it’s usually as beloved supporting characters. We are “grateful for them.” They are “great dads.” The implication is that there are many dads out there who aren’t. To say that this reinforces gender roles is an understatement. I would say that in the mamasphere as IRL, it’s taken for granted that men do more housework than they used to, but that they could do more. No momfluencer is interested in litigating this issue — we scroll through our feeds to escape reality, remember? If anything, dads in the mamasphere are being gently Shamu’d toward a distant future of domestic equality.

Sharing the work would mean sharing the credit, and that is one way that non-nuclear arrangements might challenge some of us neoliberal strivers — moms especially. I am speaking for myself here. Momfluencers sharing the household workload would need an affective script wherein they are not the queens.

Shared care work is fundamentally repetitive and routine. There is something a tiny bit boring about it - I know this from experience. When care work is shared, life becomes manageable, but from a momfluencing perspective at least, the algorithmic narrative of family heroics goes flaccid.

Making care visible on TikTok

Representation matters, right? As Walter Lippman argued, our stereotypes emerge from images we’ve been shown, not from our experiences. If the mamasphere helped us become familiar with the affective scripts of sharing care work with a group, the conversations we’d have about alternatives to a nuclear family wouldn’t be quite so speculative.

A couple of weeks ago, Jess Grose of the New York Times introduced me to cleantok: cleaning influencers on TikTok. I quickly became engrossed in the cleaning content of Monica Brady, aka @midwesternmama29. (I’m sorry I can’t embed TikToks, Substack does not seem to support it.)

Jess and I spoke at length about Monica and cleantok, and what lingered in my mind after our conversation is how subtly political it feels to have the work of cleaning rendered plainly visible on social media. Media has metabolized the politics of eating, dressing, decorating, traveling, and having a body, but cleaning is an uncharted frontier.

Cleantok is enjoyable because it’s repetitive, not despite it. It’s the routinized calm of maintenance that makes cleantok so “soothing,” which is interesting to me because on Instagram, we don’t do soothing; we do fun, adventure, joy, and triumph. There is something almost subversive about Monica Brady’s disembodied right hand clearing the dishes from the kitchen island night after night. Here it is: The shitwork your mother warned you about.

TikTok is the realm of youth, and the social constraints of the mamasphere are much looser there than on Instagram. There are new affective scripts at play on TikTok, in particular among younger women. (I will be writing about this more in the coming months because it’s a source of major delight/fascination for me.)

Maia Knight is a TikTok sensation with over 7 million followers, and she’s a young single mother of twin infants who records the mundane rituals of her day with a consistency that is a tiny bit numbing and very hard to stop watching. Sometimes Maia relies on nearby family to care for the babies while she goes out with friends. She casually refers to her cousins and aunt almost every day. She cracks a White Claw on camera before announcing that she’s going to clean the house, all without any of the defensive, nukefam wine mom scripts that can wear thin on Instagram.

Watching Maia Knight’s content feels a bit like peeking through a keyhole at how Gen Z might want to represent parenting when it’s their turn. A single mom living alone with two babies because her ex bailed before the kids were born is not exactly a rosy future towards which all teens ought to aspire, but neither is the rictus-grinning nuclear family straining under the burden of their isolation. At the very least, it’s something different.

I want to end this on a hopeful note. After all, I owe it to my mom, who did manage, at least for a little while, to raise me in a very fun non-nuclear environment. My household has acquired a copy of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s new banger, The Dawn of Everything. One of the underlying arguments of this wonderful book is that humans have always organized ourselves in ways that are quite unlike the patriarchal capitalist social order we are working our way through these days. Inequality is not inevitable, and it’s not the endgame. There have (probably!!!) been real matriarchies, and they were fun places to live, even for dudes! There have been other affective scripts and there will be again. If I see a good one in my travels, I’ll let you know.

The part about affective scripts really stood out to me. Especially "There is no gram-ready affective script for the mom who shares the work of raising kids with five other people, who is in fact not exhausted, who leaves the family for periods of work or rest without feeling guilty. What kinds of memes does this mom share with her group chat? I have no idea."

So, I'm not raising kids with 5 other people, but I do have a lot of help from my family, and although I have a full time job, my work and family life actually feel pretty balanced and don't feel burnt out. I realize that I'm incredibly privileged and lucky to be in this situation, and I'm certainly not complaining, but it does feel alienating when every "script" I see on mom Instagram is about how burnt out and tired I am supposed to be feeling - but also that I am "doing it all!" and "doing the jobs of 5 different people!"

Two thoughts came to mind as I was reading this today (okay, way more than two; two that I'm curious to hear your thoughts on):

1. We have a soon-to-be neighbor whose job is "content creator"...she has 1 million followers on Tik Tok, and 250k on Instagram, and she's a new mom. I'm now sitting here thinking through how she presents herself on these two platforms, and I know there's a difference, but I've never put my finger on it...maybe this is it?

2. I'd be super curious to read your thoughts on @cottonstem. I'll admit that my curiosity is somewhat personally motivated because I went to college with her and had mutual friends, although I would not say that WE were friends. It's been fascinating to watch her build her "brand" over the years only to shut it down completely. Is this a new thing? Is she an outlier? I don't know that this is a question specific to this essay. I often think of her when I read anything you've written.